Welty’s works provide endless avenues for scholarly analysis, and “Moon Lake” proves to be no exception.

Many of Welty’s stories revolve around life in small Southern towns, and typically indirectly confront the major social issues of gender, race, and class. “Moon Lake” specifically explores the societal consequences for transgressing socially acceptable roles.

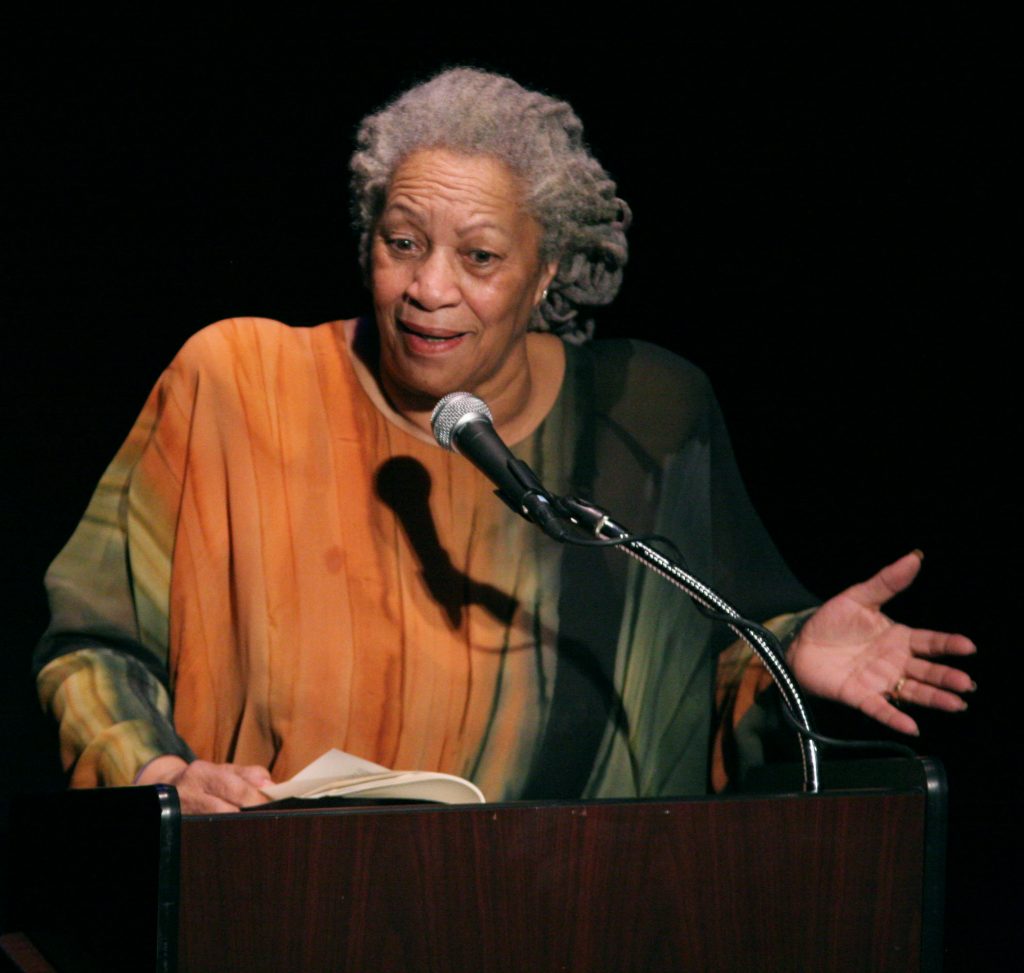

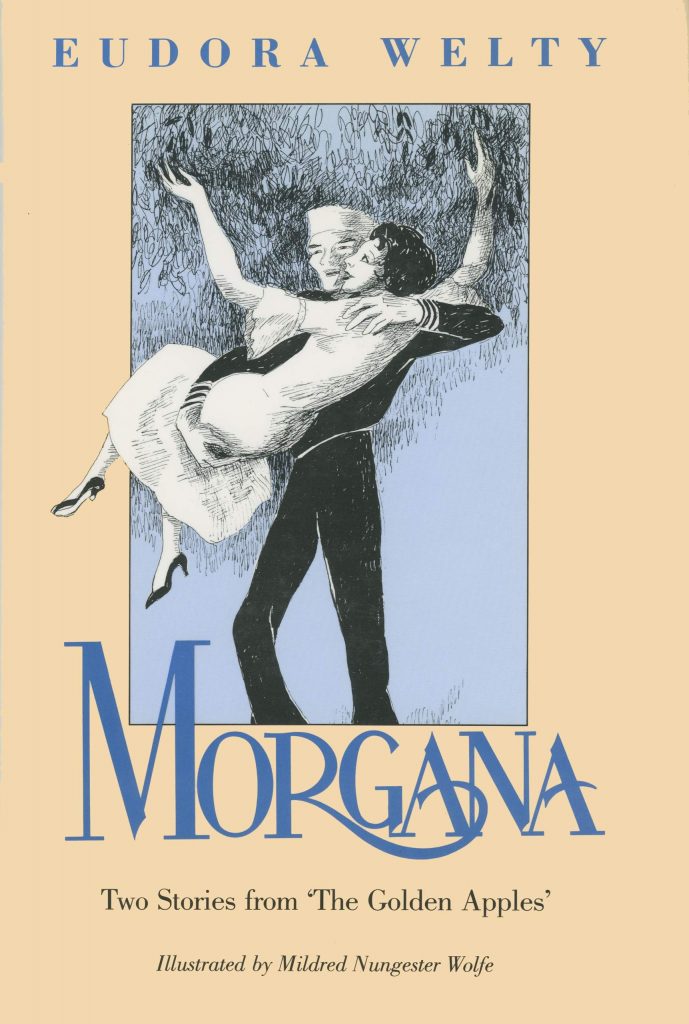

Yaeger begins the feminist discussion of “Moon Lake” in her 1985 essay “The Case of the Dangling Signifier,” a Lacanian reading of “Moon Lake” that discusses the importance of the various masculine images and signs Welty associates with the natural environment of the lake, and how the Morgana girls interact within this patriarchal setting while attempting to discover their own roles as women. In 1990, Price Caldwell argues that Morgana is not a patriarchal society, but a matriarchal one, wherein the older women teach the younger girls how to navigate patriarchal aspects of their version of reality. Costello agrees with Caldwell’s matriarchal argument ten years later, reiterating the powerful presences of Morgana’s matriarchs that reinforce strict social codes despite rebelling against male dominance. Rebecca Mark makes a compelling feminist explication of “Moon Lake,” studying the mythological intertextualities present to uncover a more empowering narrative. Sarah Peters adds historical context to her analysis, discussing the role of summer camps in reinforcing traditional gender roles in her 2012 essay.

Beginning in 2010, the discussion of race in “Moon Lake” grows. Lindsay Byron writes on the divisiveness between the white Morgana girls and the African Americans who live at “Moon Lake,” and how Easter’s independent and transgressive actions lead her to be symbolically associated with aspects of black sexuality according to the dominant white culture of Morgana. In 2013, David McWhirter and Harriet Pollack separately discuss Welty’s African American characters in a broader context, arguing that her simultaneous inclusion of and marginalization of black presences in her stories presents a realistic depiction of how racial minorities were and are treated in Southern society, allowing Welty to indirectly address racism without describing experiences she can know little to nothing about as a white woman.

Jean Griffith’s 2020 essay “Moon Lake’s Orphans and the ‘Other Way to Live’” explores the historical context of orphans throughout the 1900s. Griffith discusses the class tensions between the orphans and the Morgana girls, with charity and condescension being simultaneously present in attitudes towards the orphans. Griffith also discusses the role of Exum in Easter’s near-drowning, and how his race and class contribute to Easter’s symbolic associations with socially transgressive behaviors.

For more detailed analyses of these primary themes, read the critical summaries below.

"Moon Lake" and Gender

“Moon Lake” provides multiple opportunities for feminist readings. The differences between the Morgana girls and the orphan girls provide insight into the expectations of femininity at the time, and Loch’s graphic rescue of Easter shows further tension between expected femininity and patriarchal masculinity.

Patricia S. Yaeger’s 1982 essay, a Lacanian reading of masculine signifiers in “Moon Lake,” argues that the recurring emblems of masculinity in the story “[keep] us continually aware of the tensions between the young girls’ desires and the society which tries to shape their desires” (431). With special attention to Welty’s use of masculine imagery as a female writer, Yaeger argues that the difference between sexes primarily divides the campers. No matter where the main characters of Jinny Love, Easter, and Nina go, they are surrounded by masculine images that consistently pervade their attempts to break from traditional feminine roles maintain their androgynous innocence.

The strongest rebel against these roles, Easter, eventually endures the most for her transgressions when she nearly drowns, then suffers a graphic rescue by the only boy attending camp. Yaeger states that Welty “is collapsing the gradual and customary event of a child’s passage into our culture’s definition of ‘womanhood’ into a brief span of time,” with Loch’s passage into a higher stage of masculinity significantly less painful than Easter’s degrading experience (439, 440). Throughout the story, the girls move from the temporary and innocent experiences of girlhood to events with disturbing consequences, both emotionally and physically. Despite the harshness of Easter’s rescue, hope remains. Yaeger writes that “Nina, through her writing on the sand, her self-consciousness, and her imaginative seeing, represents the woman writer in embryo” and thus she finds a possible avenue towards free self-expression. The ending of the story, which belittles Loch, also undermines the patriarchal aspects Welty indirectly addresses.

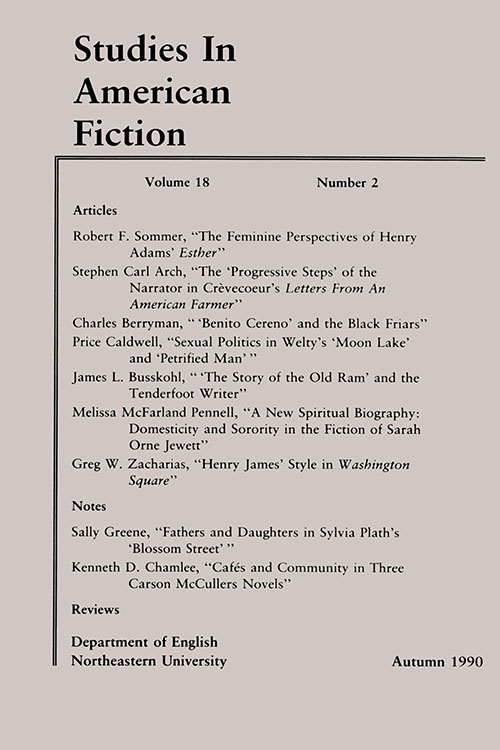

Price Caldwell analyzes “Moon Lake” in his 1990 essay “Sexual Politics in Welty’s ‘Moon Lake’ and ‘Petrified Man.’” Caldwell proposes that the society of Morgana is not patriarchal but matriarchal, arguing that “what brutalizes the young girls in that story is not a dominating male principle somehow inscribed on the landscape by culture but the paranoid effort of the mothers to subvert and to traduce an exaggerated male threat” (178). Easter, through her orphan status, rebels against the dominant maternal figures, and suffers from her “premature plunge into a reality she is not ready for” (Caldwell 172). However, the other girls will suffer more in the end, as “Nina and Jinny Love are answerable to their mothers, the women like Mrs. Gruenwald and Miss Moody and Miss Lizzy Stark who have prissified them and kept them innocent of reality” (Caldwell 172, 173). The pitiful descriptions of Loch at the end of the story further the resentment and dismissal of both him and masculinity itself by the Morgana girls, and he remains the only significant “masculine principle” in the story (179). Caldwell brings his analysis of Welty’s writing into a broader discussion of her female characters, which “try to make their men spend their energy in providing security for their wives and families rather than in the tom-fool ways they would rather spend it” to both serious and comedic ends (174). Welty can therefore criticize patriarchal components of the world while acknowledging the ways women combat or to exaggerate those components.

In 1994, Rebecca Mark explicates “Moon Lake” in a thorough examination of the myriad mythological and cultural intertextualities occurring within the story, maintaining a feminist framework. Among other observations, Mark argues that Easter’s resuscitation does not make her a victim, but rather she experiences a reemergence or regeneration of herself and finds a newfound sense of power in her womanhood. Mark diverges from the the patriarchal arguments Yaeger puts forth, and states that “Welty invents a new language,” and creates a “kind of engagement” that “creates a much more lasting and radical change because it allows the feminist author the power to resurrect herself from the waters that might have otherwise drowned her” (144). Welty does not follow commonplace narratives; instead, she creates a narrative of female agency and power.

The positive interpretations of Easter’s experience continue in 2000 with Brannon Costello’s essay “Swimming Free of the Matriarchy.” Costello also argues that Morgana and the camp at Moon Lake are matriarchal, and observes Welty’s subversion of the typical feminine associations with bodies of water, Moon Lake instead being a primarily masculine symbol. The women of the camp therefore carefully regulate the camper girls’ exposure to the lake’s waters. Costello argues, “if the male contingent at Moon Lake possesses no appreciable power, then that power must belong to the older women of the camp” (84). The various ways Lizzie Stark and Mrs. Gruenwald attempt to regulate the girls’ experiences are rejected, however, by Easter. While coming-of-age, she openly pursues her own path. Costello argues that Easter herself plans her own near-drowning, and while appearing weakened after the violence of her rescue, she still gains a sense of independence and freedom through that action. “Welty masterfully uses the recurring images of water and baptism to symbolize a breaking free of the constraints the matriarchal society places upon the citizens of Morgana,” Costello writes (92).

Sarah Peters also interprets Mrs. Gruenwald and Miss Stark as figures enforcing certain societal expectations on the girls. Placing “Moon Lake” within the context of the American summer camp movement, Peters argues that the story reflects a reaction to the formation of groups for children intended to reinforce gender roles, such as the Boy Scouts. Peters notes that “the structured activities of camp provide opportunities for adults to promote educational programs designed to shape girls and boys according to the ideals of the community” (66). However, Peters also asserts that the imagery of Welty’s writing defies any strict gendering, and in turn the camp environment becomes a liminal space allowing for the campers to explore their identities beyond the traditional boundaries and expectations of their hometown.

"Moon Lake" and Race

Living within the Deep South throughout the vast majority of the twentieth century, Welty witnessed the Civil Rights Movement and other social reforms of the era firsthand. While Welty was a known advocate for racial justice, some critics argue that her writing perpetuates negative Southern stereotypes. Welty scholar Harriet Pollack argues against one such claim, stating that “this misreading is based on assumptions not only about Welty’s relationship to her class and culture but about her relationship to gender positions and the idea of the privileged and feminine white lady” (1-2). Many aspects of Welty’s writing and language were products of her era (and she would later revise some writings to suit more modern shifts in thought), yet Welty’s approach to race typically lies in subtlety over obviousness. Pollack asserts that “the daring in Welty’s art is oblique rather than straightforward, which is not at all the same as masked, ‘hidden,’ or silent” (7). While this obliqueness draws some criticism, it allows Welty to acknowledge the treatment of African American characters through their interactions with others, the spaces they occupy, and even the space they lack. Her depictions of Southern culture remain unafraid to expose the complexities and prejudices present within the culture.

For “Moon Lake” specifically, the African American characters present are not major characters, but still provide a strong basis for conversation.

David McWhirter writes that the racist language and white perspectives in Welty’s writing present “southern white racism straightforwardly and without comment” (121). Throughout numerous stories in The Golden Apples, Welty gives readers what may initially appear to be a predominately white narrative that downplays the role of African Americans in history and in daily life. McWhirter argues, however, that “the marginalization of African Americans in The Golden Apples often works, as it does elsewhere in Welty’s oeuvre, to call our attention to the lives and histories this narrative isn’t, in any direct way, telling” (122). Yet even while Welty does not tell the stories of these characters, in not doing so she exposes how absent they are from typical representations of history and also acknowledges her own inability and experience to represent their stories properly, being an upper-class white woman. For McWhirter, “race, not class or gender, marks the self-imposed limits of [Welty’s] discourse” (124). While Welty’s stories do come close to marginalizing African Americans, she instead draws attention to and indirectly criticizes racial prejudice.

McWhirter writes, “What doesn’t happen in The Golden Apples is the sort of appropriative idealization of black subjectivity and experience we get in Faulkner’s portrayal of Dilsey in The Sound and the Fury. What we get instead are rare but crucial moments when African Americans do come into focus, not to ‘isolate white facts’ or ‘reflect’ white lives, but to identify, in however fragmentary and opaque a fashion, what Ladd describes as their capacity to ‘create change’ — to point to ‘their separateness, their dignity, and their power’” (122).

Lindsay Byron continues the discussion of “Moon Lake” specifically. Byron argues that Moon Lake itself “represent[s] sexual and racial transgression,” and Easter’s fall requires the rescue of a white boy (53). Her fall comes after “[she] refuses white masculine domination and embraces various forms of socially constructed ‘black’ sexuality, endangering her potential to ascend to middle-class white womanhood” (Byron 53). Building off of concepts created by Toni Morrison and Elaine Orr, Byron states that whiteness is socially associated with certain class and gender roles. Even though Easter is white, she cannot conform to the expected class and gender roles for a white girl, and ‘falls’ in the eyes of the Morgana residents, becoming “surrounded by associates of black sexuality” (Byron 54). Byron also examines the relationship between race structures and its relationship to ‘protecting’ a white woman’s sexuality, arguing that “the insistence upon racial loyalty necessitates not only the dehumanization of black people, but the regulation of white womanhood as well” (54, 57). The “black sexuality” Byron associates Easter with is derived from the archetype of the “fallen woman,” who “occupies a disruptive and thus necessarily silenced position within much of the literature of the South, her dire fate speaking the importance of regulating white women’s behaviors to the maintenance of white masculine domination” (57). Byron refers to figures in literature such as Edna Pontellier and Caddy Compson as examples of fallen women who inevitably face consequences for their lack of compliance to social and sexual boundaries, along with minority outsiders that ultimately fail to conform to the majority and thus face punishment. Easter and Exum both suffer for their low positions in the dominant power structure, which ignores the large variety of people forced to exist within it (Byron 62).

Written in 2013, Laura Schrock’s essay focuses on how white femininity in Welty’s stories emphasizes the societal treatment of African American characters, especially African American men. Schrock writes that “moving beyond the treatment of black characters in Welty’s work as merely atmospheric or ‘decorative’ allows for an explanation of their active role in constituting her depictions of American selfhood “(95-95). Also discussing “Sir Rabbit,” Schrock describes the language surrounding the character Exum from “Moon Lake” extensively. The emasculation and othering of Exum emphasize the power of Loch’s white masculinity, and helps to shape the girls’ white female sexuality. Schrock ends her argument by stating: “Welty demonstrates how the systematic stratification of racial and gender privilege that characterizes the white American consciousness owes its perpetuation to the white woman as well as to the white man” (113).

Jean Griffith’s essay also provides an interesting reading concerning the Exum. One of few black characters in “Moon Lake,” Exum is the young boy assumedly responsible for Easter’s perilous fall into Moon Lake’s waters. Even though he is only a child and initially considered “insignificant,” the Morgana girls come to associate him with “the stereotypical oversexed black man” who threatens “white womanhood” (Griffith 91). Even though Exum is only a mischievous child, his actions take on a “racial and sexual context . . . for those who witness it,” in accordance to the dominant prejudices (Griffith 92).

"Moon Lake" and Class

Class tensions prove quite relevant within the web of social structures present in “Moon Lake” and other Welty works. As with racial and gender roles, the transgression of and exploration of different class roles present crucial talking points for the story. Lindsay Byron’s essay associates Easter’s lack of compliance to the middle-class values of Morgana to her outsider status, an observation validated by critics such as Caldwell, who adds that Easter’s orphanhood gives her a certain sense of freedom the other girls do not.

Joan Griffith applies historical context to Easter’s role. Many children were taken to orphanages following the Civil War and throughout the early 1900s because their working-class parents were unable to afford them (Griffith 80). As a result, the connotations of being an orphan shifted. A parent-less child created sympathy, but the children of poor families admitted to orphanages and asylums had a greater stigma attached to them. Easter can be assumed to be part of the latter group, as she recalls herself a memory of her mother dropping her off at the orphanage at a young age (Welty 431). Applying this history to Welty, Griffith states that “perhaps this is why the impressions Nina and the others have of Easter are of more concern in ‘Moon Lake’ than Easter herself is: children like Welty’s ‘orphans’ revealed the coexistence of conflicting attitudes towards the poor, wherein sympathy for them (especially in theory) competed with condescension and disparagement” (81). The “distrust,” as Griffith repeatedly refers to it, between the upper class and the lower class shapes the interactions of the Morgana girls with the orphan girls.

The contrasting language used with the Morgana campers versus the orphans and the negative treatment of the orphans by the Morgana girls both provide evidence for class tensions. Griffith argues that “in their ignorance of or disregard for much of what the Morgana girls take for granted — they cannot swim, they have never heard of the game Casino, and their names are ones that ‘no one around here’ has — ‘Moon Lake’s’ orphans, if not misfits, certainly do not seem acculturated to the society around them” (83). The involvement of Easter and the other orphans at the summer camp reflects the misguided attempts at instilling middle-class culture and values into lower-class children who will likely never experience the same world of leisure and ease that those of a higher social stratum exist in. (Griffith 84-85).

Easter’s social position as an orphan, according to Griffith, makes her vulnerable despite her whiteness (93). Easter may represent the idea of social freedom for Nina and the other Morgana campers, but her fall into the lake, with its sexualized overtones and brutal rescue, shows her fragility within the world as a young girl. Griffith writes, “previously resentful of [Easter’s] aloofness, [the Morgana campers] begin to resent her vulnerability” (94). The girls grow tired of her, and when Easter returns to consciousness, she is not the source of curiosity and power she once was, a fact reinforced by Lizzie Stark. As the matriarch of Morgana and therefore the enforcer of its social norms, Miss Stark’s disgust of Loch’s rescue and dismissal of Easter’s importance come to define the moment for the Morgana girls. Griffith argues that Miss Stark “symbolizes the comfort to be found in conforming to those [social] boundaries” (95). Even Nina, who dares to think about what life would be like to be someone other than a girl from Morgana, eventually conforms to the values Lizzie Stark represents, despite Miss Stark being in a position expected to aid charitable endeavors.

In 2019 Mackenzie Balken elaborates on the ‘otherness’ of the orphan girls. Drawing from scholarship on the effects of trauma, Balken asserts that being orphaned, whether through parental deaths or abandonment, leads to a trauma that distinguishes the orphans as separate from the kin-based society of Morgana. Easter’s ability to create her own narrative, as seen through her independence and naming of herself, expands both Easter’s understanding of herself as well as others’ understanding of her. Balken writes that “through its depiction of Easter’s self-narration as a means of overcoming the trauma that she has experienced as an orphaned, othered character, “Moon Lake” provides a figure who is representative of all of the girls at the summer camp in the liminal space between childhood and adulthood” (15). Nina, in discovering Easter’s narrative, gains a better understanding of Easter’s experiences while also having the revelation that she will never fully be able to know what it is like to be an orphan or ‘other,’ but will one day be separate from her familiar familial structure.

Works Cited

Balken, Mackenzie. “Seeing Self Otherwise: Orphaned Otherness and the Power of Narrative in Eudora Welty’s ‘Moon Lake.’” South Central Review, vol. 36, no. 1, 2019, p. 1-18. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/scr.2019.0000.

Byron, Lindsay. “Falling into Blackness: Race, Class, and Female Transgression in Eudora Welty’s ‘Moon Lake.’” Eudora Welty Review, vol. 2, 2010, pp. 53–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24742224. Accessed 28 July 2020.

Caldwell, Price. “Sexual Politics in Welty’s ‘Moon Lake’ and ‘Petrified Man.’” Studies in American Fiction, vol. 18, no. 2, 1990, pp. 171–181., doi:10.1353/saf.1990.0015.

Costello, Brannon. “Swimming Free of the Matriarchy: Sexual Baptism and Feminine Individuality in Eudora Welty’s ‘The Golden Apples.’” The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 33, no. 1, 2000, pp. 82–93. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20078283. Accessed 29 July 2020.

Griffith, Jean C. “Moon Lake’s Orphans and the ‘Other Way to Live.’” New Essays on Eudora Welty, Class, and Race, edited by Harriet Pollack, University Press of Mississippi, 2020, pp. 79-101.

Mark, Rebecca. The Dragon’s Blood: Feminist Intertextuality in Eudora Welty’s ‘The Golden Apples,’ University Press of Mississippi, 1994.

McWhirter, David. “Secret Agents: Welty’s African Americans.” Eudora Welty, Whiteness, and Race, edited by Harriet Pollack, University of Georgia Press, 2013, pp. 114–130.

Pollack, Harriet. “Reading Welty on Whiteness and Race.” Eudora Welty, Whiteness, and Race, edited by Harriet Pollack, University of Georgia Press, 2013, pp. 1-22.

Yaeger, Patricia. “The Case of the Dangling Signifier: Phallic Imagery in Eudora Welty’s ‘Moon Lake.’” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 28, 1982, pp. 431-452. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/441253. Accessed 6 June 2020.

Further Reading

Arnold, Marilyn. “The Edge of Adolescence in Eudora Welty’s ‘Moon Lake.’” Southern Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 1, 1993, pp. 49-61. Arnold considers the story “in the context of the initiation of youth into adult knowledge,” exploring the relationships between the setting of “Moon Lake” and the different social and biological factors at work (49). The setting, like the campers themselves, exists at a threshold between unknown wilderness, or adulthood, and set social boundaries. Arnold notably departs from Yaeger’s feminist reading of Easter’s resurrection, taking a more positive connotation from the scene. While noting its brutality, Arnold argues that Welty projects a certain sense of beauty in Easter’s revival and the knowledge gained from it, which Nina eventually attempts to reject.

Bayne, John. “Textual Variants in ‘Moon Lake.’” Eudora Welty Newsletter, vol. 24, no. 1, 2000, pp. 12–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43949211. Accessed 14 Aug. 2020. Bayne analyzes the textual differences between the original version of “Moon Lake” published in The Sewanee Review in 1949 and The Golden Apples version of the story, published later that year, as well as later revisions appearing in Welty’s Collected Stories. The majority of these differences were made so “Moon Lake” would be better integrated into the world of The Golden Apples or for the sake of clarity.

Harrison, Suzan. “Playing with Fire: Women’s Sexuality and Artistry in Virginia Woolf’s ‘Mrs. Dalloway’ and Eudora Welty’s ‘The Golden Apples.’” The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 2, 2003, pp. 289–313. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26476706. Accessed 3 Sept. 2020. Harrison compares and contrasts the ways in which feminine sexuality correlates to feminine creativity in the works of Welty and Woolf. Concerning “Moon Lake,” Harrison asserts that Nina’s adolescent attraction to Easter is partially grounded in Easter’s lack of adherence to societal gender roles. She also states that “Nina’s imaginative act [in imagining ‘the other way to live’], an act of transformation, of transgressing the boundaries of identity, even of sex, is markedly similar to Eudora Welty’s description of her own imagination” (304). When Easter is rescued by Loch, it transfers creative powers in a dangerous way; Easter becomes passive and Nina’s creative power is diminished.

Kreyling, Michael. Eudora Welty’s Achievement of Order, Louisiana State University Press, 1980. Kreyling dissects the rich intertextualities and other connecting factors that unify Welty’s works and the technical intricacies of her writing, including the multiple mythological allusions in The Golden Apples. Concerning “Moon Lake,” Kreyling observes the unifying themes and parallel characterizations between “Moon Lake” and “June Recital,” specifically comparing Easter and Nina to Virgie and Cassie. He states that, by the end of the story, Nina “is sharply aware of her own incompleteness” as is Cassie at the end of “June Recital” (91).

Mortimer, Gail, “Musical Echoes of World War I in Welty’s ‘Moon Lake,'” Eudora Welty Newsletter, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 11-12. Mortimer observes the references to music from World War I. Set in the 1920s, “Moon Lake” features two songs sung by WWI soldiers. The first, “Mr. Dip Dip Dip” is based off of the wartime song “Mr. Zip Zip Zip,” and the second song, “Pack Up Your Troubles,” appears near the end of the story. Mortimer observes the other army-like practices of the campers, such as the reveille, and comments that Welty likely was influenced by the very recent experiences of World War II. By including the references to war in her story, Welty was exploring the full and subtle impact of war even on children’s camps.

Pugh, Elaine Upton. “The Duality of Morgana: The Making of Virgie’s Vision, the Vision of The Golden Apples.” Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 28, no. 3, 1982, pp. 435-451. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26281230. Accessed 3 September 2020. Pugh makes a compelling argument for the archetypes of light and dark, or the “golden apples of the sun” and “silver apples of the moon” that emerge through various character dynamics in The Golden Apples (436). In “Moon Lake,” this dichotomy shows itself through Nina and Easter. Nina, associated with the sun and the order and clarity it represents, is challenged by Easter, associated with the darker and freer archetypes of the night. Ran MacLain is also associated with “figure of the night, passion, [and] instinct” (440).